This past week I watched the most significant film I’ve seen in the last few years: Come and See, a 1985 Soviet-era anti-war film. Taking place in what is now Belarus in 1943, the film traces a few epic, devastating days in the life of a teenager who “joins” the local Soviet resistance to German incursions.

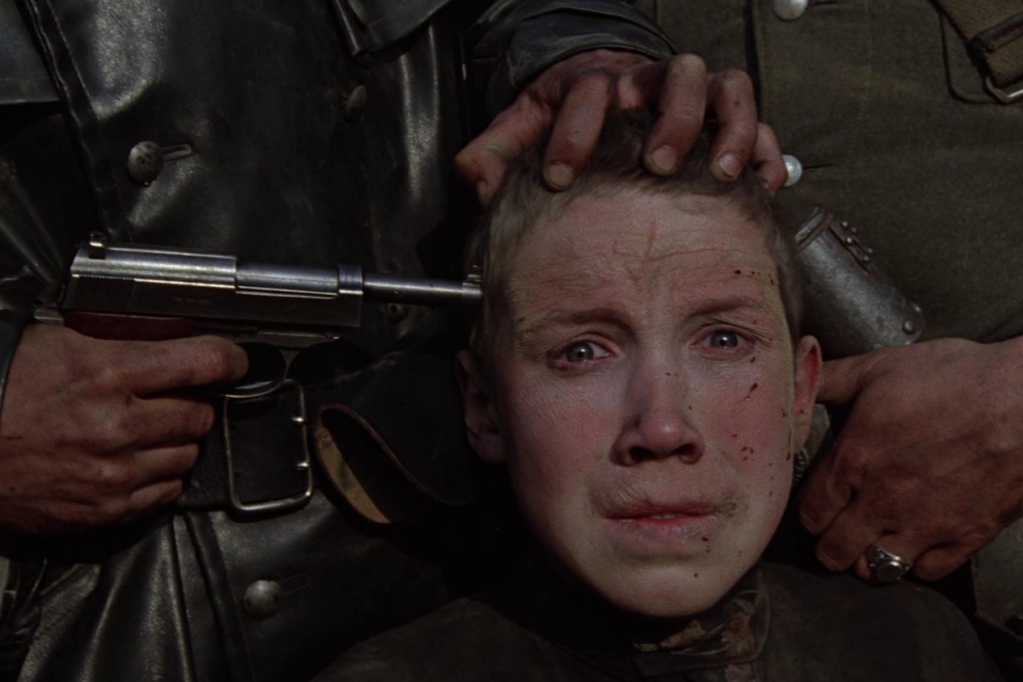

I will not spoil the power of this film by giving too much away. I will say that this film, at its core, shows the radical transformation of a smiling, whimsical, 13 or 14 year old boy into a gray, hollow wreck in a matter of hours. His heart and mind are smashed against the brutality around him. He sees not only death up close but also the horrendous inhumanity that war brings forth in our species. Scenes of almost fairy-tale light and mood give way to instances of the most egregious forms of torture, humiliation, and murder. We witness these acts conducted by carousing, laughing, crazed soldiers, while inhabiting the view of our protagonist, Florya.

Aleksey Kravchenko’s performance as Florya is beyond incredible. To think he was able to inhabit this character at the age of 14 is amazing, and I can’t imagine that he escaped the production without some trauma. Many sources claim live ammo was used, and he was certainly very close to real incendiary devices, raging fires, and extremely gory depictions of dead people. His performance was beyond things such as honors or awards. Simply legendary.

For a significant portion of the film Florya is thrown together with Glasha, a strange, beautiful young woman who sometimes sees and says what Florya can’t. There are several intense scenes between the two characters. One, where they dance in raindrops after narrowly escaping death is contrasted with a later sequence where they struggle neck-deep in a bog, frantic and animalistic.

The film is built using historical accounts as its backbone, but there are threads of magic realism here as well. Certain moments strike me as direct references to iconic moments in film classics, such as the sliced eyeball in Un Chien Andalou (1929) or the screaming nurse in Battleship Potemkin (1925). But the piece is a work entirely singular and unique. There are moments unlike any I’ve seen, and from my cursory exploration online I can see that many of the most important cinematographers and directors of photography in film cite it as an influence.

The thing about watching Come and See right now – and why it’s essential viewing – is that it highlights the Russian war against Ukraine in stark ways. One reason this film got past the Soviet censorship machine was that it demonstrated the pure barbarity of the German invasion. But it is easy to understand that the filmmaker, Elem Klimov, was making a broader point about what war – both in terms of materiel and the political machinations behind it – does to people. There is an cold, bloody irony in the fact that a Russian film from the late Cold War era shows the illegitimacy of Russian warmongering today. There are young men and women, just like Florya and Glasha, lying dead on the streets and countryside of Ukraine right now, and their deaths are every bit as criminal as those depicted in Come and See.

So, yes. Come and see, and then reject evil of war.

Main website for the film at Criterion Collection.

More info about the film on Wikipedia.